Mystery symbols on historical Werribee building

At the Werribee Historical Society, in the National Trust historic building located on the corner of Watton Street and Duncans Road, Werribee, Victoria is a rectangular stone with some rather unusual engravings, as shown below (all photographs are courtesy of the Werribee Historical Society). The stone measures approximately 109cm (43”) long by 18cm (7”) wide at the mid-point

Plate 1: The Werribee ‘mystery stone’ approximately 109cm (l) x 18cm (w)

According to Lance Pritchard, secretary of the Werribee Historical Society, the stone was originally discovered on a local farm owned by the one family for several generations. It is surmised the stoned existed on the property, far from any known existing road, prior to the family’s occupation of the land.

This stone was found in association with other stones that appeared to make up the foundations of a small building of around 4 metres x 4 metres. The stone appeared to be located as an entrance step into the building, which would have meant the engravings would have been located towards the outside edge of the step. This would suggest the engravings would have been visible to people passing over the step, if they were to look down before passing over the threshold.

Placed wide apart, it would suggest the symbols were deliberately positioned so they would not be stepped upon while passing across the stone.

Plate 2: The engraving to the left of the ‘mystery stone’, approximately 13cm wide

Plate 3: The engraving to the right of the ‘mystery stone’, approximately 10cm wide

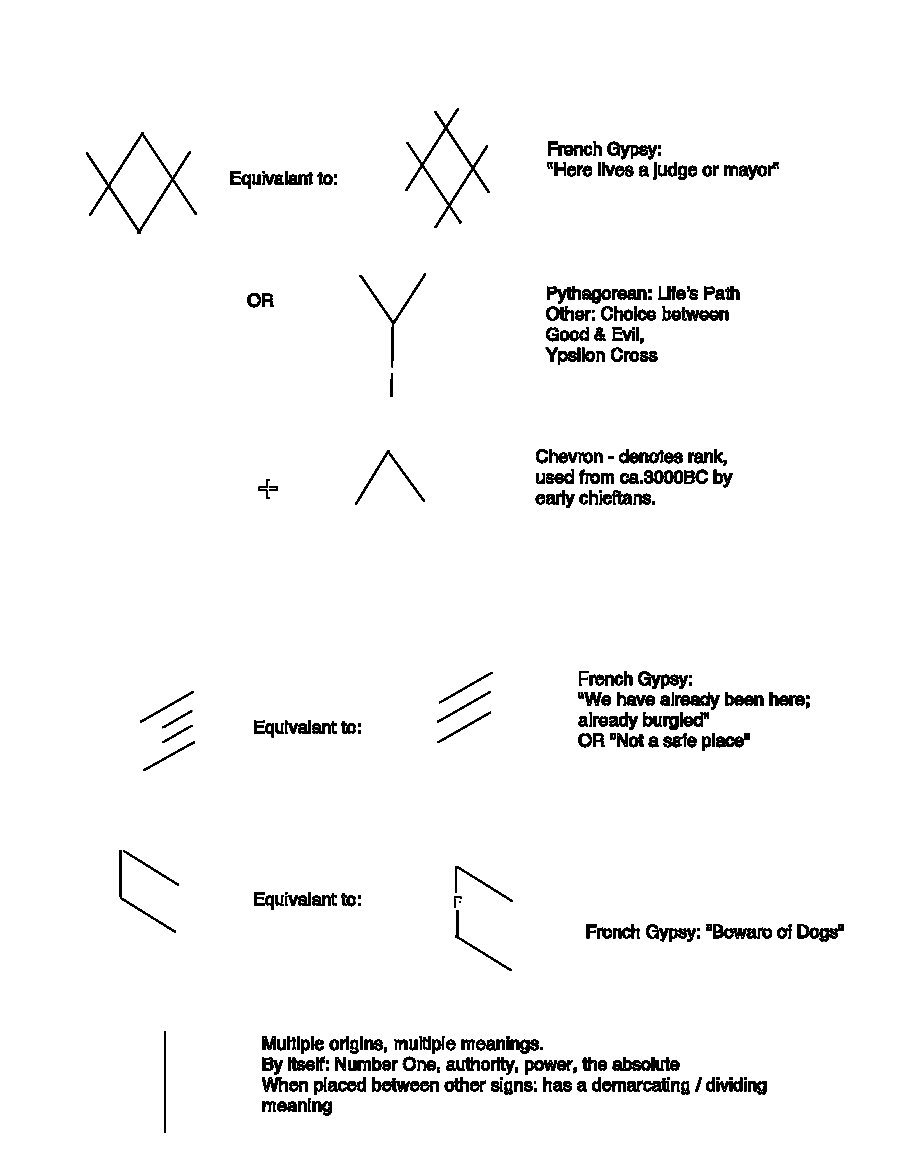

Plate 4: Possible meanings and origins of the symbols

Plate 5: Possible meanings and origins of the symbols

Based on the combination of symbols as depicted, the engraving to the left hand side (Plate 2) is related to symbols common to the French Gypsy and suggests that a person of authority is present at this abode. This may have been a deterrent to wanderers to stay away or keep out from the property, but may have also been the building owner’s way of claiming the land he occupied.

The two triangles on the right hand side (Plate 3) suggest an invocation to God for protection from bad or unknown spirits and intruders, success in the farmers’ endeavours and accompanying wealth. An appeal to the divine for rain and water is an understandable request in an unknown land.

Why would an immigrant farmer engrave symbols such as these on his threshold?

If we place the stone and its engravings within the context of the early settlement of the Werribee district, it seems to be a rather rational thing to do.

Prior to government surveys and recorded land sales, squatters illegally occupied crown grazing land beyond the prescribed settlement areas. After 1840, they were able to claim land for farms by paying a lease to the Crown, which officially held all real property title (Encylopedia Britannica). However, by the 1850s with a large influx of migrants spurred on by the gold rush and wanting to settle, the sale of ‘selections’ forced squatters to compete against prospective farmers. If a squatter was wealthy enough, he could purchase the land he leased, otherwise he and his family would be forced off the land they had worked(ibid).

Throughout the UK and Europe, illiteracy was high in the lower social and economic classes. Learning a common symbolic language, such as French Gypsy, is a practical solution for people who want or need to communicate information but cannot do so with the written word.

As with any language it has the disadvantage that people not taught how to read it find it alien and possibly could think it has links with Paganism, witchcraft or other ‘demonic’ cultures. It would be the same as a person from another time thinking today’s symbology, such as a biohazard warning sign, was a mark of devil worship.

As this ideography is no longer used within Australia, it provides a physical link with the early days of immigrant settlement and gives an insight as to how information was able to be conveyed in a largely illiterate community. It is an important part of early history in the Werribee district.

Disclaimer:

The interpretations and the possible matching up of the symbols are based on Carl G Liungman’s work on semiotics of western symbols. It is possible for other meanings and better matching symbols to exist, although none could be found during the preliminary research.

While some of the symbols do not match exactly to Liungman’s symbols, it is likely that the time from between when the stone was created and Liungman collected his research that several small changes had occurred in the expression of the ideograms.

All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Trudy White

BA(Hons) Archaeology & Palaeoanthropology

T.L. White Heritage Consulting Service

Berwick VIC 3806

E: tlw.hcs@gmail.com

References:

Encyclopedia Britannica

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/561757/squatter

Accessed 24 March 2014

Liungman, C. G. (1995). Thought Signs. The semiotics of symbols – western non-pictorial ideograms. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press.

Werribee Historical Society

Cnr Watton Street and Duncans Road, Werribee VIC 3030